“Whose Pet Is It, Anyway?” was first featured in The Publication of the California Veterinary Medical Association Newsletter: Volume 74 – Number 3

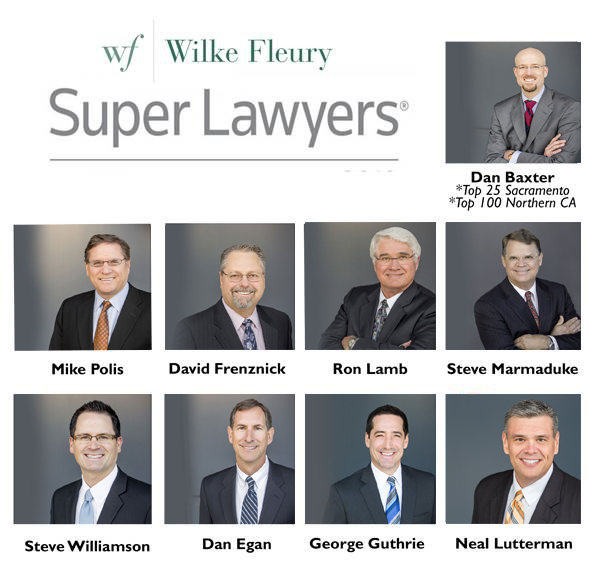

By: Dan Baxter

As most readers of California Veterinarian know, the law firm at which I work provides thirty minutes of free monthly advice to CVMA members with legal inquiries. Most of those inquiries center around employment-related issues and issues arising out of veterinarian/client/patient interactions.

In the latter category is a scenario involving competing claims to animal patients that has produced questions to me and my colleagues from several veterinarians in recent months. Specifically, what should a veterinarian do when more than one ostensible “owner” seeks to take possession of the animal upon its release?

In one hypothetical, “Mittens” is delivered to Clinic by Jane and left there for treatment. At some point during Mittens’ stay, Clinic receives a call from John claiming to be Mittens’ “real” owner, and claims that Mittens should only be released to him rather than Jane. Jane returns to Clinic to pick up Mittens, insists that she is the “real” owner, and demands release of Mittens into her custody.

One can craft many variations to this hypothetical, from joint delivery of Mittens to Clinic by both Jane and John, to Clinic records that clearly identify Mittens owner as one or the other (or both), to introduction of another person entirely into the fray. Regardless of the hypothetical’s nuances, what should a veterinarian do when faced with competing claims to possession of an animal patient?

Fortunately, there is guidance….

Figure It Out, People!

But before we get to that guidance, let’s begin with some practical advice. Each instance in which competing possessory claims are brought to a veterinarian’s doorstep represents an occasion in which animal owners are trying to make their problem your problem. Not only does a Jane/John imbroglio over ownership and possession place the veterinarian in an uncomfortable position from a client service standpoint, it effectively asks the veterinarian to make a quasi-legal judgment call as to who is the true “owner.” The “losing” client will naturally hold the veterinarian responsible for this decision, and various business-related ramifications may ensue, from the cessation of that client’s business, to negative social media reviews, to possible VMB and/or legal complaints.

For these reasons, the first step to take when faced with competing claims is to place the ball back into Jane and John’s court. In our above hypothetical, if Mittens remains at the clinic, Jane is indicating that Mittens should only be released to her, and vice versa relative to John, the veterinarian should issue a clear communication—preferably in writing—to Jane and John describing the situation, and directing them to figure it out between themselves. Such a communique should be direct, concise, and forceful, in the manner of the following:

Jane and John:

Yesterday, Mittens was brought for treatment at our clinic. Following that treatment, we received instructions from each of you that Mittens was only to be released to you, and not to the other. While we value both of you and appreciate your love for Mittens, your competing instructions place us in the unfair and untenable situation of entering a dispute that only you can resolve. Therefore, we request that you jointly come to the Clinic today or tomorrow to pick up Mittens, or otherwise reach a resolution between yourselves as to who will do so. In absence of such a joint decision by you, we will have no choice but to act in conformity with the requirements imposed by the Veterinary Medicine Practice Act.

Please respond as soon as possible.

–Dr. Wendy Smith

More often then not, a communication like the above will bear fruit. Generally speaking, Jane and John will realize the difficulty of the situation from the veterinarian’s point of view, and understand that is good for neither Mittens, nor the veterinarian, nor Jane and John themselves, for the situation to go unresolved. Moreover, by invoking “The Law”—in this case, the VMPA—the veterinarian raises the specter of an undesirable outcome outside of Jane and John’s control. That potential loss of “say” over the outcome will generally produce the cooperation necessary to settle matters.

What Does the Law Say?

But what if matters remain unresolved? What does the VMPA actually tell us about how to manage this situation?

The answer comes to us from 16 Cal. Code Regs. section 2032.1, which deals with the veterinary-client-patient relationship (“VCPR”) and how it is created. While a full discussion of Section 2032.1’s terms is unnecessary to this article, suffice it to say that the existence of a VCPR is specific to the clinical course at issue. In that vein, Section 2032.1(b) requires the veterinarian to have “sufficient knowledge of the animal(s) to initiate at least a general or preliminary diagnosis of the medical condition of the animal(s),” and further requires the veterinarian to communicate with the client “a course of treatment appropriate to the circumstance.” This regulatory language shows that a VCPR is not a singular event that covers treatment of an individual animal for all time, but a relationship that operates on a condition-by-condition and circumstance-by-circumstance basis.

Why is this relevant to a discussion of competing possessory claims to an animal? Because it effectively removes the question of legal ownership from the veterinarian’s calculus. Returning to our above hypothetical, if Jane is the person who delivered Mittens to Clinic for the treatment at issue, then Jane is the person through whom a VCPR was created. Accordingly, if Jane and John find themselves at impasse relative to Mittens’ release even after a Clinic communication of the type recommended above, then Mittens should be released to Jane alone, as she is the “client” for relevant purposes. Tweaking the hypothetical, if Jane and John had jointly delivered Mittens to Clinic, then Clinic may release Mittens to either of them.

In either hypothetical, or different permutations thereof, a VCPR-centric determination of the issue renders irrelevant the validity of John’s (and Jane’s) claim of “real” ownership, and ultimately relieves—at least from a legal standpoint—the veterinarian from being the arbiter of Jane and John’s possessory dispute. Moreover, should the “losing” claimant be so dissatisfied with the veterinarian’s determination as to file a VMB complaint or take other legal action, there is a good argument that the veterinarian’s acts consistent with Section 2032.1 would provide “safe harbor” against an adverse determination against the veterinarian.

This same “safe harbor” argument applies in a variety other of ownership-related disputes (which oftentimes are found between divorcing couples), including the following:

• Medical Records: After Jane brings Mittens to clinic, John calls Clinic, states that there has been a relationship split and that Mittens is now ‘his,” and requests that Mittens’ medical records not be released to Jane. However, because the VCPR is with Jane, Clinic’s obligations relative to the records flow to Jane, not John.

• Treatment-Related Discussions: Similarly, after Jane brings Mittens to clinic, John calls Clinic stating that he—and not Jane—is the owner, and that Clinic should not provide any further information to Jane concerning Mittens’ care, treatment, condition, progress, etc. Once again, since Jane brought Mittens to Clinic, the VCPR is with Jane, not John.

• “Stray” Animals: Jane brings Mittens to Clinic claiming Mittens is a stray, and leaves Mittens at Clinic for treatment. Then, John appears at Clinic claiming to be Mittens’ owner and demands return of Mittens to him, as well as a summary of Mittens’ records. Here, too, the VCPR is with Jane, not John, such that Clinic has no obligations to John.

Conclusion

In the end, clear communication is key, and the likelihood is that most competing possessory claims will be resolved through a short and plain statement like that composed above. However, if communicative efforts fall short, let your path forward be guided by the provisions of Section 2032.1, and the parameters of the VCPR.